Newsletter Issue 68 - October 2014

In this issue:

Supreme Court protects cable

Copyright and tattoo art

Death of the software patent

Ask Dr. Copyright ...

Dear Doc:

Since you wrote about Aereo, that company with the millions of TV

antennas that was going to free us from the tyranny of Comcast,

Verizon, Time-Warner, Cox, and all of the other blood-sucking video

vampires, and the fact that Aereo lost big-time in the Supreme

Court, we have been waiting for the next chapter. So what gives?

Signed,

Walter White and Tony Soprano

Dear Walt and Tony:

Fear not! The Aereo saga continues, and it's gotten even stranger

since those six Honorable Justices of the Supreme Court shut down

the service in June.

You may remember (and if not, you can read the Doc's June 28th

column) that Aereo argued that it was just a remote antenna and DVR,

not a cable service, and so, it did not have to pay royalties to

television broadcasters. That made sense to judges in New York, but

in Washington, DC, not so much. The Supreme Court reasoned that

technological differences make no difference. If Aereo's service

looked like the kind of cable service that Congress wanted to

restrict, then, by gum, it was legally the same (never mind those

millions of tiny antennas, tuners, hard drives, and the fact that

you can legally time and space shift broadcast television under the

Sony Betamax ruling by an earlier Supreme Court.)

As the Court said, "why should any of these technological

differences matter? They concern the behind-the-scenes way in which

Aereo delivers television programming to its viewers' screens. ...

Why would a subscriber who wishes to watch a television show care

much whether images and sounds are delivered to his screen via a

large multisubscriber antenna or one small dedicated antenna,

whether they arrive instantaneously or after a few seconds' delay,

or whether they are transmitted directly or after a personal copy is

made?"

Okey-dokey, said Aereo...if that's what the Court says, then we'll

just be a cable company, pay royalties to the broadcasters, and pass

those fees on to our subscribers. After all, competition in the

market is what the good ol' USofA is all about, right? Now, you'd

think that the TV guys would be pleased to have more money, and that

would be the end of it, but no, here's where the story gets even

more bizarre.

Aereo's Position: The Supremes said that we walk like a duck, and

quack like a duck, so we are legally a duck. We now agree, so we are

going to use the compulsory license provisions of the Copyright Act

to allow us to retransmit over-the-air programs to our customers. We

will, of course, pay for that right as the law requires. Done and

done.

The TV Guys: No so fast, Aereo. You're NOT a cable TV company, and

you can't use the law that the Supreme Court says you violated to

stay in business by paying us. You have to stop. You can't show our

programs. Not in real time, and not even by time-shifting. We demand

an injunction from the trial court. Now!

The District Court considered the issues carefully. Judge Allison

Nathan then issued a 17 page order effectively shutting down Aereo.

Why, you ask?

Well, to put it bluntly, it's not good enough even if Aero agrees

with the Supreme Court, and offers to pay. Judge Nathan reasoned

that "Aereo's argument suffers from the fallacy that simply because

an entity performs copyrighted works in a way similar to cable

systems it must then be deemed a cable system for all other purposes

of the Copyright Act." And, unfortunately for Aereo, an earlier

decision of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals had already

determined that Congress never intended that Internet transmissions

of video should be called cable television for purposes of the

Copyright Act.

WPIX, Inc. v. ivi, Inc. (Perhaps the Supremes didn't

read that one).

So, Judge Nathan issued an order prohibiting Aereo from transmitting

any TV program on its system while that program was being broadcast

(leaving, for the moment, the question of whether Aereo's DVR

function could remain online.)

Aereo, like other innovators such as Uber, Lyft, and AirBnb, is

faced with laws and judicial interpretations that look squarely

backward, while their business models try to look to the future. So

there you have it (or rather, you don't, and won't anytime soon.)

The Doc suggests that you call your cable company for service. That

way, at least you'll be home between November 1st and 15th between

the hours of 6am and 9pm, and that will keep you out of trouble.

Have a question about some intellectual property dilemma? The

attorneys at LW&H actually like to think about such things (even

though it sometimes makes their heads hurt.) Give them a call.

Until next month (or not)... Don't stop believin'.

The "Doc"

Fixed in a Tangible Medium ... Tattoo Art

Now that sporting a tattoo has gone mainstream, it would

only stand to reason - - given that tattoos are creative expressions

fixed in a tangible medium (skin) - - that tattoo artists seek

protection of their designs under copyright law. To date, few

copyright cases involving tattoos have been filed but we've learned

that video game companies, in particular, are not taking chances.

Here's some background.

First, why you may ask is a tattoo deserving of copyright

protection?

Section 102 of the Copyright Act provides protection

for "original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of

expression." "Works of authorship" include a number of categories,

including pictorial and graphic works. There should be little

controversy that a tattoo design is equivalent to a graphic or

pictorial work and that skin is a tangible medium of expression.

The question of determining "originality" would be the same as for

any graphic work. But once created, who owns the image? The

customer or the artist? Copyright law would assign ownership rights

to the artist unless there is a license or assignment of the rights

to the customer. There are other interesting issues. Could

photographs of the wearer in which the tattoos are visible be

actionable copyright infringements? What about video games? NBA

stars, for example, adorn themselves with tattoos. Do video game

companies need a license to portray the stars and their tattoos and,

if so, from whom do they obtain licenses, the wearer or the

artist?

In 2011, in perhaps the first lawsuit of its kind, Victor Whitmill,

a tattoo artist -- most notable for creating the Maori inspired

tattoo on the side of Mike Tysons's face -- sued Warner Brothers

Entertainment in an attempt to stop the release of the movie

"Hangover Part II" in which one of the characters was tattooed in

identical manner to that of Mike Tyson. Whitmill claimed copyright

infringement resulting from the film's promotional activities

showing the tattoo, demanded that release of the movie be stopped,

and other costs and damages.

The judge agreed that Mr. Whitmill had "lost control over the image

he created" and that Whitmill had a legitimate copyright claim in

his tattoo design, Yet, the court refused to grant Mr. Whitmill's

request for a preliminary injunction ruling that "the public

interest does favor protecting the thousands of other business

people in the country as well as Warner Brothers" connected to the

film and its promotion.

The parties eventually settle

Though not the final word on the matter, the court's decision sets

the stage d.for similar type actions by those seeking to protect tattoo

designs.

As result of this lawsuit -- and good business sense -- certain

media companies and sport groups, according to the

Wall Street

Journal, weren't taking chances. The NFL players Association was

urging athletes to obtain licenses for their body art and Electronic

Arts (EA) reported that for its latest video game "Madden NFL 15",

that it scanned images of tattoos only from after getting legal

authorization from the artist who drew them. Apparently, tattoo

artists are more than willing to sign releases when presented to

them by sports athletes.

If you'd like to learn more about the legal basis for claiming

copyright protection in tattoo art, don't hesitate to call the

lawyers at Lipton, Weinberger & Husick.

Another One Bites the Dust!

In the not-so-slow death spiral of software patents in light of

the Supreme Court's recent decision in Alice v CLS Bank, another

trial court has determined that a patent for software should not

have been issued because the software addressed by the patent is not

the kind of invention eligible for patenting.

In the case of Amdocs v Openet Telecom, the Federal district court

considered whether inventions directed to software for reporting

usage of network devices on a computer network could be patentable.

The court applied the two-part test of Alice v CLS Bank: first,

does the challenged patent claim address an abstract idea; second,

does the claim include 'something more' to transform the abstract

idea into something that is patent-eligible. The court's answer to

the first question was 'yes' and to the second question was 'no,'

rendering the patents unenforceable.

The claims in question addressed a purely software product that does

nothing outside of a computer. What the software product does

inside the computer did not seem to be of much interest to the

court. If the Amdocs decision becomes the norm, then patents for

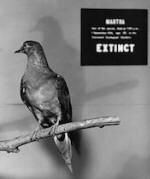

software will be only a dusty footnote, like the passenger pigeon.