Newsletter Issue 53 - July 2013

In this issue:

Fair use in copyright

Removing material from social media

Attack on intellectual property

Non-disclosure agreements

Ask Dr. Copyright

Dear Doc:

I know you've explained the legal concept of "fair use" before, but

I have a question about that. Does it infringe an author's copyright

in a book to paraphrase one sentence from the book in a movie, if

you give credit to the author, or is it fair use?

Sincerely,

Absolom Absolom, Mississippi

Dear AbAb:

Funny you would ask that question, since it is a paraphrase of one

asked by United States District Judge Michael P. Mills in his recent

decision in

Faulkner Literary Rights LLC v. Sony. In that suit, the heirs of

William Faulkner sued Sony Pictures, which distributed Woody Allen's

movie

Midnight in Paris. In the movie, Owen Wilson's character

paraphrases Faulkner's novel, Requiem for a Nun, when he says, "The

past is not dead. Actually, it's not even past. You know who said

that? Faulkner, and he was right. I met him too. I ran into him at a

dinner party."

The actual sentences from the novel are, "The past is never dead.

It's not even past."

Given the obvious and serious legal issues at stake, the Faulkner

heirs sued for violation of the Lanham Act and the Copyright Act. On

a motion by Sony to dismiss the case, the judge read the book,

watched the movie, and expressed his gratitude that he had not been

asked to compare The Sound and the Fury with

Sharknado.

The legal question, however, turned on what the Court saw as, "(1)

whether the affirmative defense raised to the copyright infringement

claim can properly be considered on a motion to dismiss; (2) whether

the use in Midnight is justified under a de minimis copyright

analysis; (3) if the alleged infringement is not de minimis, whether

or not it constitutes fair use; (4) whether Faulkner's Lanham Act

claim has merit."

Judge Mills, in his 17 page memorandum opinion, gives a textbook

lesson in fair use analysis. It all really comes down in the end,

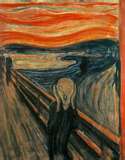

however, to his belief that Woody Allen has created a,

"transmogrification in medium" by taking a sentence from the novel

and using it in a different medium (film) and for a different

literary purpose. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary,

"transmogrify" means, "to change or alter greatly and often with

grotesque or humorous effect." Ahhhh... so THAT's what Woody Allen

did!

So you see, Ab, it's fair to misquote a famous author of serious

literature, if you do it in film, with comic effect. So I guess, we

can try it in a law firm newsletter, too... As Woody Allen once

said, "I believe there is something out there watching us.

Unfortunately, it's the government." (But then again, that's a real

quote.)

If you need to paraphrase a famous person, it would be good to check

with the attorneys at LW&H - they're not quite famous, but they do

know a lot about copyright law.

Until next month...

The "Doc"

The DMCA to the Rescue (Maybe) ...

In a recent embarrassing

broadcast by KTVU television of San Francisco, the morning

anchor, Tori Campbell, identified the pilots of the recent San

Francisco Asiana airline crash as "Captain Sum Ting Wong," "Wi Tu

Lo," "Ho Lee Fuk," and "Bang Ding Ow." As she read the names,

Campbell didn't flinch and, even more perplexing, why didn't the

station snag the racist script before airing it? To its credit, KTVU

made a quick public apology and

fired some employees. The station was still faced with a

newscast gone viral. Just how would they remove all the copies of

the broadcast on YouTube and other popular web sites?

Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) to the rescue! Under the

DMCA, a 1998 amendment to the US Copyright Act, copyright owners may

request online service providers to take down works, which have been

posted online without the owner's permission. We have written about

take down notices in previous posts. Service providers generally

obey such requests to avoid liability for the illegal acts of their

online subscribers. And so, under the theory that the video posters

had essentially stolen copies of the embarrassing newscast, KTVU

undertook a "successful" campaign of sending "take down notices" to

various web sites such as YouTube. But how successful were they?

Well, if you really wanted to see the broadcast, you could find it

on Bit Torrent and other file sharing sources but for the mainstream

web surfers, KTVU's campaign appeared largely successful.

KTVU may have been satisfied, but copyright lawyers were not. There

is a very compelling argument that the KTVU newscast was not

protected by copyright law at all. Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright

Act places limitations on the exclusive rights granted by the Act.

Copies of works used for purposes such as criticism, comment

(including parody), and news reporting are not, under the Section

107, infringing. Rather, such use constitutes "fair use." Certainly,

most people who posted copies of the broadcast did so for no purpose

other than criticism, comment, news or parody even it they thought

it was funny. If they were posted for racist purposes, perhaps, KTVU

has an argument but many, if not the majority of postings, were

comments upon the stupidity and poor management of the KTVU

newsroom. Based on the fair use theory, bloggers at

The Desk submitted counter-notifications with YouTube demanding

that the KTVU videos be reinstated. They were apparently successful

given that the broadcast is still available

here. The KTVU incident, nevertheless, demonstrates how creative

use of copyright law can be used for reputation management even if

the results are short-lived.

New Rules, New Strategies for Innovators

The past 15 years have seen an unprecedented attack on patents

and patent-owners in the United States. Orchestrated by foreign

nations, multinational corporations, and a variety of other groups,

largely funded by similar vested interests, this attack has reduced

much of the value formerly associated with patented innovations. In

past issues of our newsletter we have described how patent owners

can no longer realistically expect to block sales of products that

infringe their patents through the injunction process, how

infringers can conspire to divide patented processes among several

actors to avoid infringement, how multiple infringers must now be

sued separately, rather than joined in a single action, and how

delays at the Patent Office and increasing fees put university

researchers, solo inventors, and small companies at a disadvantage.

We have also been counseling our clients to help them construct

valuable patent strategies.

In the latest round of anti-patent actions, a committee of the

Federal Courts including some noted judges and attorneys has issued

a

model order that they recommend be adopted by federal trial

courts to govern patent suits. Such model orders are usually adopted

quickly and without significant change by courts around the country.

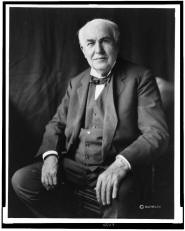

What is troubling about the present document, "A MODEL ORDER

LIMITING EXCESS PATENT CLAIMS AND PRIOR ART" is that for the history

of our patent system, which dates back to the time of Thomas

Jefferson, inventors have always been able to present claims in as

much detail as they wish, so that their patents would clearly and

particularly cover all aspects of their inventions, and, at least

since the 1950s, inventors and their attorneys have been required by

both the Patent Law and the rules of the Patent Office to submit

every relevant item of prior art of which they were aware. The

background of the model order cites a study that shows that

litigated patents contain an average of 24 claims, and cite 31 prior

art references, which the committee calls, "problematically

excessive."

Some recent cases have seen individual judges impose limits on

patent owners, requiring that they limit the number of patents in a

suit, and that they throw away claims in the patents that they

assert to reach some arbitrarily small number. In other cases, the

number of products accused of infringement has been limited by court

order. All of this trimming is claimed to streamline cases and to

promote the administration of justice. In reality, however, such

rules are evidence that our judicial system often fails to handle

the technical complexity of our modern technological world. When it

takes teams of hundreds of researchers years of effort to develop

and commercialize complex inventions such as synthetic proteins,

chips with millions of components, and software with tens of

millions of lines of code, the refusal of our courts to expend the

mental energy needed to understand and to protect such innovations

harms innovators. For courts to say to inventors, you have done the

hard work of creating value, but we require you to be able to

explain it to judges and juries in monosyllabic terms, and to

choose, "not more than ten claims from each patent, and not more

than a total of 32 claims," means that for some inventors, they will

have a more difficult task to defend the value that they create.

Inventors must and will respond. Already, we are counseling clients

to submit more patent applications with fewer claims per

application. In litigation, the proposed limits will mean that

separate law suits will have to be filed on small groups of patents

against the same defendant. The erosion of the patent system has

caused some innovators to opt for trade secrecy, at least in part,

rather than patenting every aspect of their inventions, and this

impoverishes our entire society, because it keeps technical advances

out of the public view, which slows follow-on innovation.

We are confident that Americans will continue to innovate, despite

the limits being imposed on the patent system. We are confident that

we, and others who value our tradition of individual innovation will

continue to find strategies to protect the value generated by

inventors. Because we believe in the long-term value of innovation

and the patent system that protects innovation, we at LW&H continue

to develop new strategies for our clients, and particularly

university researchers, garage inventors, startup companies, and

established concerns to implement effective and efficient legal

strategies for protecting their inventions.

So You Think Your Trade Secrets Are Protected...

It's time for a story. We'll start with the moral - read your

non-disclosure agreements and comply with ALL of the requirements of

the agreement to keep your information secret. Back to the story:

In license negotiations for an invention, Convolve and another party

signed a non-disclosure agreement. Like many non-disclosure

agreements, the agreement required that the person disclosing secret

information designate the information as confidential. Convolve

revealed trade secrets to the other party in reliance on the

agreement, but failed to designate the trade secrets as

confidential. The license negotiations fell through and,

predictably, the other party used the trade secrets. Convolve sued,

arguing that the trade secrets were protected by the non-disclosure

agreement and also by trade secret law.

Convolve lost on the trade secret claims, both at trial and on

appeal. The

Federal Circuit Court of Appeals held that Convolve's failure to

designate the trade secrets as confidential according to the

agreement meant that the trade secrets were not covered by the

agreement. The other party was free to use the trade secrets in any

way that it desired.

Convolve also lost on its trade secret law claims. The Federal

Circuit held that the agreement trumped trade secret law. In short,

Convolve waived its other trade secret rights by signing the

non-disclosure agreement.

In the give-and-take of a business negotiation, information can be

disclosed in all sorts of ways - verbally over lunch, in e-mails or

texts, in demonstrations and plant tours. Some of the information

disclosed will be confidential and some will not. You and every

person on your team who communicates with another party under a

non-disclosure agreement MUST be aware of what information is

confidential and the necessary steps to protect the confidential

information under a non-disclosure agreement.

If you are the party disclosing information, another way to protect

yourself is to make sure that the agreement protects all disclosed

information without requiring a specific designation and that the

rights of the disclosing party are in addition to its rights under

trade secret law.