Newsletter Issue 46 - December 2012

In this issue:

California Online Privacy Protection Act

Is a copyright notice required?

When will a court issue an order to stop patent

infringement?

Unified European Patent

Privacy in the Age of Apps

If you use or develop online software or smartphone "apps" then you need to know about CalOPPA. No, that's not some form of steam-driven musical device from an old-time carousel. It's the California Online Privacy Protection Act, and it has very real consequences for any company that does business online. This month, the State of California sued Delta Airlines for failure to comply with CalOPPA, and the suit seeks $2.500 for EACH TIME the Fly Delta mobile app was downloaded!

To comply with CalOPPA, you need to figure out if your online system or app collects any personally identifiable information ("PII") such as a name, email address, physical address, telephone number, IP address, current location, or sensitive information such as a social security number. Next, you have to know the target age range for your web page or app. If it's under 13, you need to talk to an attorney ASAP. There are special rules that apply.

Next you need a list of every party that will have access to the PII that you collect. You then need to specify how the user can control that PII. Can they view what you've collected, edit it, and delete it from your database? You then need a written policy that you will display to anyone from whom you collect PII that explains what you collect, how you intend to use it, with whom you may share it, and what the user can do to view, change or delete his own PII in your systems. You may want to review the sample policies available from the Center for Democracy and Technology, which has a very complete template, and then have your attorney review your policy after you're done drafting it. Finally, you may wish to get certified by a third party like TrustE so that you tell your users that you're trustworthy with their PII.

Compliance with privacy regulations also varies in other countries, but these basic steps are the minimum necessary for any developer. If you need a hand, the attorneys at Lipton, Weinberger & Husick can help to draft these kinds of policies, and others. Give them a call.

Notice or Not: ©

In late November, David Pogue of the New York Times wrote about a hoaxer who plastered Facebook sites with an unsolicited message that stated:

In response to the new Facebook guidelines, I hereby declare that my copyright is attached to all of my personal details, illustrations, comics, paintings, crafts, professional photos and videos, etc. (as a result of the Berner [sic] Convention).

For commercial use of the above my written consent is needed at all times.

Facebook is now an open capital entity. All members are recommended to publish a notice like this, or if you prefer, you may copy and paste this version.

Pogue was correct in referring to the posting as a "hoax", noting that the warning or notice makes no difference to the legal status of your illustrations, comics, paintings, crafts, professional photos and videos. But why was he correct?

Under the Berne Convention, an international copyright treaty, authors and creators are not required to post a copyright notice or warning as a prerequisite to enforcing their copyrights. Before adoption of the Berne Convention in 1988, if a copyright owner in the United States failed to place a copyright notice -- the ubiquitous © -- the owner would lose all his rights in the work should there be an infringement. Click this link to review the official word of the U.S. Copyright Office on this subject. Adoption of the Berne convention brought the United States into sync with the rest of world's copyright practice. So, in summary, Copyright is a "self-executing" right that arises as soon as a work is "fixed in a tangible medium." The rights created by copyright law are no longer predicated upon the author's posting or marking his work with a copyright notice.

Nonetheless, lawyers sill advise their clients to apply a notice. That's because it still serves a purpose. In the United States, a copyright owner has the right to obtain "statutory damages" for infringement. These are damages that are set forth in the U.S. Copyright Statute and which are set at different amounts for intentional and unintentional ("innocent") infringement. If you apply a copyright notice to your work, an infringer cannot claim "innocent infringement." That's because the infringer was on notice that you were the copyright owner. In an infringement action this could mean the difference between receiving as much as $100,000 dollars per intentional infringement versus $200 dollars per innocent infringement.

So, like David Pogue said, you don't need a fancy notice to enforce your rights ("registration" helps but that's a subject for another newsletter article). However, using the © symbol along with the date and your name serves a purpose.

© 2012 Lipton Weinberger & Husick

When is a Patent Owner Entitled to a Court Order Stopping

Infringement?

Consider this scenario: you have gone to all the time and expense to obtain a patent from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, like Apple, which obtained the design patent at right. You have launched your product and your sales are good. Now a pirate, say, Samsung, is copying your product and stealing your sales. Are you entitled to a court order stopping infringement of your patent?

Before the U.S. Supreme Court decided the case of eBay v MercExchange in 2006, the answer would have been a resounding 'yes.' After the eBay case, the patent holder must demonstrate, among other things, 'irreparable harm' from the infringement and that an award of money damages to the patent holder is not enough to compensate the patent holder. It is not enough to show harm - the patent holder must show that copying of the features specifically protected by the patent caused the harm.

The most recent application of the eBay decision is the ongoing worldwide Apple v Samsung litigation. Apple recently proved that among other things Samsung copied Apple's patented designs for the iPhone and iPad. Apple was awarded a money judgment for $1.049 billion (that's billion, with a 'b'). The trial judge decided on December 17 that Apple is not entitled to an injunction stopping Samsung from selling the infringing products. The judge concluded that Apple did not show that the harm to Apple resulted from the specific infringement in question. Apple still has the right to appeal the denial of the injunction to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals. Stay tuned.

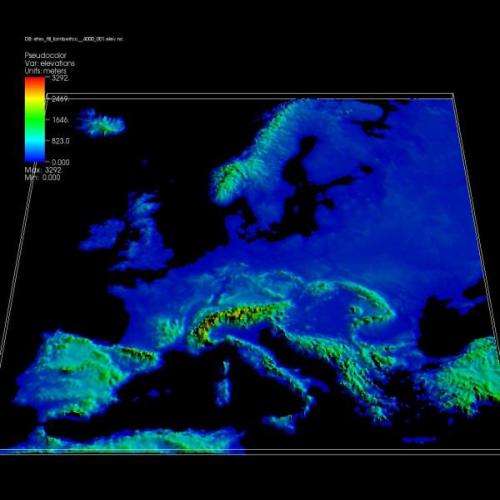

Unified European Patent

If you want to protect a product by patent in Europe today, you generally will file an application in the European Patent Office ("EPO"). When your application is (eventually) reviewed and approved by the EPO, you then must register the approved application with each individual European country in which you desire a patent and must file any translations required by the individual country. The actual patents are issued by the individual countries and are enforced in the courts of the individual countries. You must pay 'annuities' every year to each individual country to maintain the patent in effect in that country. The process is time consuming, duplicative, and expensive.

All of that is about to change. The European Parliament has passed a regulation to create a 'Unified Patent' to be issued by the EPO and enforced by centralized European courts. The Unified Patent will bypass the registration process in individual countries, avoid translation expenses, avoid local annuities, and avoid the need to file multiple lawsuits in multiple countries to either enforce or attack a patent. To take effect, the new system must be ratified by thirteen European Union member states including France, Germany and the UK.

Italy and Spain are not in agreement with the Unitary Patent regulation and likely will not participate.