Newsletter Issue 24 - February 2011

In this issue:

Is Coca-Cola's trade secret

recipe still a trade secret?

Watson computer vs. Jeopardy champions

What's in a

name? - Your name as a trade mark

Patent Reform Legislation forwarded to the full U.S. Senate

Federal Courts' Continued Hostility Toward Complex Patent Issues

Is Coca-Cola's Trade Secret Recipe still a Trade Secret?

The recipe for Coca-Cola® is one of the most valuable trade secrets

in the world. As a trade secret, it is not protected by patent,

copyright, trademark or any other government-granted monopoly. The

recipe is a trade secret only because The Coca-Cola Company keeps

the information secret.

The recipe for Coca-Cola® is one of the most valuable trade secrets

in the world. As a trade secret, it is not protected by patent,

copyright, trademark or any other government-granted monopoly. The

recipe is a trade secret only because The Coca-Cola Company keeps

the information secret.

According to the radio show 'This American Life,' the cola cat is out of the bag. According to the show's producers, a photograph of the original 1886 recipe appeared in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1979 and is fully legible. Does publication of this 125 year old recipe destroy The Coca-Cola Company's trade secret?

Hmm. John S. Pemberton, who invented Coca-Cola®, was a wounded Confederate veteran, pharmacist and morphine addict. After the Civil War, Pemberton sold an alcoholic product that included caffeine and cocaine as a medication for, among other things, morphine addiction. He changed the recipe in 1886 to remove the alcohol in response to temperance laws and changed the name to "Coca-Cola®." Pemberton sold his rights and died in 1888, still an addict. The cocaine was gone from the recipe by 1903, but the caffeine remains.

So what about the secret recipe for Coca-Cola®?

In general, a trade secret is entitled to protection in the courts only so long as the owner of the trade secret takes reasonable precautions to keep the information secret. If someone else acquires the information, then that person is free to use the information, so long as the person did not acquire the information through improper means, as a result of a breach of confidence, or as the result of a mistake. For example, stealing the recipe would be improper means . Acquiring the recipe by hiring a Coca-Cola Company executive who knows the trade secrets would be a breach of confidence.

The Coca-Cola Company has made no allegation that the original 125

year old recipe was stolen or acquired by anything other than proper

means. The old recipe is not subject to trade secret protection and

may be copied freely- just don't expect to mix up a modern Coke®.

The modern recipe is still a trade secret.

Robert Yarbrough

Elementary, My Dear Watson

On February 14-16, 2011, we watched

"Watson", an IBM system of

computers the size of a two-car garage, compete against the all-time

best champions on the game show Jeopardy!®. On subjects from

diseases to characters in Beatles® songs, the computer was

impressive, pressing the buzzer faster than its human opponents, and

getting so many answers correct that its occasional gaffe seemed

like a deliberate act designed to preserve the hope and dignity of

our species. The technology was impressive! In just a few years,

systems like Watson will fit in our mobile phones (making today's

"smart" phones seem like stone tools.) We will come to rely on their

ability to parse language and retrieve factual information as a way

to extend our own memories, just as we now have electronic

organizers that help us to remember phone numbers and appointments.

On February 14-16, 2011, we watched

"Watson", an IBM system of

computers the size of a two-car garage, compete against the all-time

best champions on the game show Jeopardy!®. On subjects from

diseases to characters in Beatles® songs, the computer was

impressive, pressing the buzzer faster than its human opponents, and

getting so many answers correct that its occasional gaffe seemed

like a deliberate act designed to preserve the hope and dignity of

our species. The technology was impressive! In just a few years,

systems like Watson will fit in our mobile phones (making today's

"smart" phones seem like stone tools.) We will come to rely on their

ability to parse language and retrieve factual information as a way

to extend our own memories, just as we now have electronic

organizers that help us to remember phone numbers and appointments.

It is clear that we will soon see uses of Watson-type systems that will greatly advance how easily we perform a number of common tasks. For instance, Watson interprets the "questions" (answers, actually) on Jeopardy! with very powerful algorithms that seem to understand human language. This part of the system will find immediate employment in technical and customer support systems, where just understanding the question and figuring out who (or what) should provide assistance is more than half the battle. Watson's ability to quickly search a large and diverse database, and to weigh the probable correct answers will also prove valuable as a decision tool. Just having the top three probable responses to choose among in difficult situations will help us in areas as different as picking a mortgage, routing air traffic, and diagnosing diseases.

Looking beneath the "hood" however, the real-world flaws in Watson are readily apparent to those with a background in computer databases, search and natural language processing (ok, well, to me, at least, since these fields were central to my system designs for my first company, Infonautics, and its product, "Homework Helper", way back in 1990.) First, Watson relies on a professionally-constructed database of information. Want to beat Watson at Jeopardy? Just make it search the Internet in addition to its own databanks. The mass of conflicting data, divergent views, outright lies, and incomplete reference in which we live our lives is still well-beyond the capability of even our smartest machines. Watson may be able to compute a clue, but when it comes to humor, sarcasm, inuendo, and propaganda, Watson is clueless. Next, show Watson a painting as a clue, and ask not who painted it, and when, but what it means, or what feeling it evokes. To humans, the Mona Lisa's smile is inscrutable. To Watson, every work of art is just a catalog entry.

All of this is not a criticism of Watson or its creators. It is, however, a criticism of those who conclude that when it comes to intelligence, if Watson can beat Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter, it is "game over" for our species, and we are weeks away from SkyNet, the malevolent computer network of the Terminator movies that takes over the world. In a recent article in the National Law Journal, Robert C. Weber, IBM General Counsel wrote about using Watson's technology to aid in the courtroom. "If a witness says something that doesn't seem credible, you can have an associate check it for accuracy on the spot." Lawyers already know that human memory is faulty, and that eyewitness testimony is unreliable. Juries don't. How will juries respond when attorneys can point out every flaw, every miscue in a witness narrative? This is not a question of whether our legal system should use technology - it does, and it should, to provide the best quality of counsel to our clients. Mr. Weber continued, "Deep QA [Watson's programming to understand questions] won't ever replace attorneys; after all, the essence of good lawyering is mature and sound reasoning, and there's simply no way a machine can match the knowledge and ability to reason of a smart, well-educated and deeply experienced human being. But the technology can unquestionably extend our capabilities and help us perform better."

The question for our society is how we value those things that

Watson cannot compute and factor them into our resolution of

disputes - dignity, respect, integrity, altrusim. Until we can add

those to Watson's programming, the humans in the system need to

value and uphold the human values that so-often get lost in the law.

Lawrence Husick

What's in a name? - Your name as a trade mark

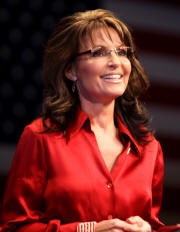

By now you may have heard that

Sarah Palin and Bristol Palin have

each filed applications in the United States Patent and Trademark

Office ("PTO") to register their individual names as federal

trademarks. Sarah identified her services as "information about

political issues... Educational and entertainment services, namely

providing motivational speaking services in the field of politics,

culture, business and values." Bristol described her services as

"educational and entertainment services, namely providing

motivational speaking services in the field of life choices." Their

trademark applications were initially rejected for failure to

provide the appropriate signatures. Nonetheless, this is an error

that is easily overcome.

By now you may have heard that

Sarah Palin and Bristol Palin have

each filed applications in the United States Patent and Trademark

Office ("PTO") to register their individual names as federal

trademarks. Sarah identified her services as "information about

political issues... Educational and entertainment services, namely

providing motivational speaking services in the field of politics,

culture, business and values." Bristol described her services as

"educational and entertainment services, namely providing

motivational speaking services in the field of life choices." Their

trademark applications were initially rejected for failure to

provide the appropriate signatures. Nonetheless, this is an error

that is easily overcome.

Though it may seem that trademarking one's name is the height of narcissism, it is actually a common practice, and a necessary one at that. The fashion world, for example, is full of personal name trademarks: Chanel, Levis, Versace, Gucci are but a few examples. Registration offers a degree of protection from those who wish to exploit a personal name without the owner's permission. On the other hand, if you're famous, it does not prevent others from using your name in the context of commentary, satire, critique, or news reporting.

Under U.S. trademark law, the general rule is that because personal names are considered descriptive, they are not registrable unless the applicant demonstrates that his or her name has "acquired distinctiveness." Acquired distinctiveness means that over time, the consuming public associates the personal name mark with the goods or services, identified by the mark. If the public perceives the personal name as just a personal name, it has not acquired distinctiveness. The PTO has a set of established rules to determine whether a surname is "primarily merely a surname" and thus not registrable. The PTO will look at

(1) whether the surname is rare;

(2) whether the term is the surname of anyone connected with the

applicant;

(3) whether the term has any recognized meaning other than as a

surname

(4) whether it has the "look and feel" of a surname; and

(5) whether the stylization of lettering is distinctive enough to

create a separate commercial impression

If the name to be registered is that of a living person, written consent must also be provided. In fact, Sarah Palin's trademark registration was initially refused because she had not provided written consent to the registration by providing her signature. To summarize, a personal name mark is registrable if it is not merely a surname, if it has acquired distinctiveness, and it has the consent of the living individual (if applicable).

Once a personal name earns trademark status, it can also become

problematical. Take for example, the circuitous case of Joseph

Abboud who registered his personal name as a trademark identifying

men's apparel. In 1988 he licensed his trademark to JA Apparel in a

joint venture and signed a non-compete agreement. Abboud left the

business in 2005 and, after his non-compete agreement expired,

started his own line of clothing name "jazz," which he identified as

a "new composition by designer Joseph Abboud." JA Apparel filed suit

against Abboud for trademark infringement. The court decided in

favor of JA Apparel despite Joseph Abboud's fair use argument. The

court enjoined Abboud from using his name as a trademark in a manner

that would result in a likelihood of confusion with the trademarks

owned by JA Apparel. Abboud appealed the decision, resulting in the

remand of the case back to

District Court, which eventually upheld

its earlier injunction but permitted Abboud to make fair use of his

name in a business context so long as he avoided using it as a

trademark. So beware, one you sell your name to the devil, you may

not get it back.

Adam Garson

Patent Reform Legislation forwarded to the full U.S. Senate

The proposed

Patent Reform Act of 2011 and will be considered by the

full Senate when it reconvenes beginning today, February 28. Final

passage of the bill is not assured and similar bills have been

reported out of committee twice in recent years.

The proposed

Patent Reform Act of 2011 and will be considered by the

full Senate when it reconvenes beginning today, February 28. Final

passage of the bill is not assured and similar bills have been

reported out of committee twice in recent years.

The bill includes several provisions that are unfriendly to small

business patent owners and independent inventors; namely, moving to

a first-to-file system rather than the current first-to-invent

system, limiting damages for patent infringement and allowing

post-grant opposition to patents. The bill generally makes it harder

for an applicant to obtain a patent and more difficult to enforce

the patent after it is issued.

The patent reform legislation generally has been supported by

companies, particularly in the technology sector, that are frequent

targets of patent infringement litigation and that believe that the

patent system is tilted too far in favor of inventors. The

legislation is generally opposed by individual inventors and those

favoring a strong patent system.

Robert Yarbrough

Federal Courts' Continued Hostility Toward Complex Patent Issues

In the recently-decided case of

In re Katz Interactive Call

Processing Patent Litigation, the Court of Appeals for the Federal

Circuit (which hears all appeals of patent cases) determined that

trial courts may limit the number of patent claims that may be

asserted by a patent owner in a litigation, regardless of the

complexity of the invention or the number of defendants who

allegedly infringe the patent. This decision is yet-another example

of the unwillingness of the Courts to take on the often-intricate

issues involved in patent enforcement litigation.

In the recently-decided case of

In re Katz Interactive Call

Processing Patent Litigation, the Court of Appeals for the Federal

Circuit (which hears all appeals of patent cases) determined that

trial courts may limit the number of patent claims that may be

asserted by a patent owner in a litigation, regardless of the

complexity of the invention or the number of defendants who

allegedly infringe the patent. This decision is yet-another example

of the unwillingness of the Courts to take on the often-intricate

issues involved in patent enforcement litigation.

The Katz case involved 25 cases filed against 165 defendants, and 31 patents covering call processing systems that are commonly used by companies operating customer service call centers. The 31 patents contained a total of 1,975 claims. (The number of claims per patent was much larger than average, but the courts have previously ruled that there is no limit on the number of claims that an inventor may file, as long as the fees are paid to the Patent Office.)

The trial court, citing a need to efficiently manage the combined multidistrict litigation, ruled that Katz had to limit his case to 64 of his claims, and Katz appealed the ruling, claiming that the court had denied him due process and deprived him of property rights (by not allowing him to enforce his other claims.) Katz knew that claims not asserted could not be enforced later because of other rules.

The Court of Appeals ruled against Katz, stating that Katz, "has failed to demonstrate that the allocation of burdens in the claim selection procedure adopted by the district court unfairly prejudiced it by creating a significant risk that Katz would be erroneously deprived of property rights in unselected claims." The Court said that because some claims were duplicative of others, Katz had to identify those claims that raised separate legal issues. This ruling seems to conflict with prior decisions that state that separate issued claims are presumed to differ from each other.

While there may be simple procedural explanations for the Katz

decision, inventors and patent owners should beware that having a

large number of claims that cover a complex invention may cause

judges to run for cover, rather than to impartially preside over an

attempt to enforce the patent in litigation.

Lawrence Husick