'Inequitable Conduct' as a Defense to Patent Infringement

Robert J. Yarbrough

2008 and 2011

A. Introduction

‘Inequitable conduct’ is a shield against patent liability and is a defense frequently raised in patent infringement litigation. This memorandum provides an overview of the historical roots and current development of ‘inequitable conduct.’

The doctrine of ‘inequitable conduct’ is entirely judge-made. The sources of our inquiry necessarily are court decisions.

B. The Early Years

The doctrine of ‘Inequitable conduct’ is based on the law of equity. Equity refers to the ancient power of a court to issue an injunction to order someone to do something (for example, an injunction ordering someone to stop infringing a patent). Under the historical law of equity, a person is denied an injunction if the person has ‘unclean hands;’ that is, if the person does not deserve the injunction because of past bad deeds of the person, regardless of the merit of the person’s claim. The early cases to deal with the misdeeds of a patent holder addressed egregious fraud in terms of ‘unclean hands:’

1. , 290 US 240 (1933)

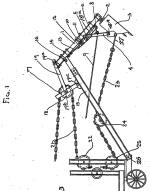

Keystone owned five patents for a ditching machine and initiated infringement litigation. The plaintiff had suppressed information of prior use of the invention. The Supreme Court denied equitable injunctive relief to the plaintiff based on unclean hands.

2. ., 322 U.S. 238 (1944)

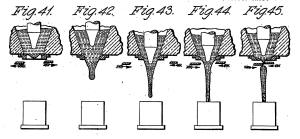

Hartford applied for a patent for an automated

glass-making machine and the application was rejected. To

overcome the rejection, Hartford’s attorneys generated a

magazine article touting the device as ‘revolutionary’ and

secured publication of the article under a false author. The

published article was submitted to the PTO to overcome the

rejection and the patent issued.

a false author. The

published article was submitted to the PTO to overcome the

rejection and the patent issued.

Hartford subsequently sued Hazel for infringement. The trial court found no infringement and Hartford appealed. On appeal, Hartford argued the article and won. Hazel smelled a rat, but eventually capitulated and paid $1,000,000.00 to Hartford. Hartford induced the false author of the article to lie to Hazel’s investigators.

In the course of an anti-trust investigation, the deception was uncovered. Hazel asked the Circuit Court to reopen the case. The Circuit Court determined that the article was not the only reason that it found for the plaintiff in the earlier litigation and refused to reopen the matter. The Supreme Court reversed, holding that the injury was to the public, not just one litigant. The remedy: “… calls for nothing less than a complete denial of relief to Hartford for the claimed infringement of the patent thereby procured and enforced.”

From this case forward, the doctrine of ‘inequitable conduct’ left its equity roots behind and precluded not just injunctive relief, but all enforcement of the tainted patent.

3. 324 U.S. 806

U.S. 816 (1945)

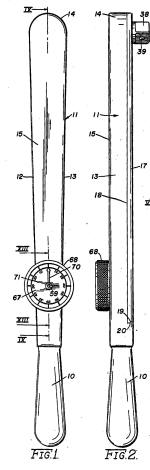

Precision held patents relating to torque wrenches and

initiated infringement litigation. The defendants defended

in equity based on ‘unclean hands.’ The term ‘inequitable

conduct’ as applied to patents first appears in this case.

Precision’s patent was based on a false claim of

inventorship. A principal inventor was actually an employee

of Automotive. Precision falsified information and secured

perjured testimony to win an interference with a patent

application filed by Automotive. The falsity of the

information was subsequently discovered and Precision

assigned its rights in the issued patent to Automotive.

Automotive sought to enforce the patent. The Supreme Court

refused to allow the fraudulently-obtained patent to be

enforced.

Automotive was not the miscreant here, but was nonetheless denied relief. The and holdings together signal that the property right represented by a patent is only as valid as the process used to create the patent in the first place. If the process was fraudulent, the property right is unenforceable and hence does not exist, no matter who is seeking to enforce that right.

C. Modern Approach to Inequitable Conduct

As recited in many of the Federal Circuit cases to consider the issue, a party challenging a patent based on ‘inequitable conduct’ must establish two elements by “clear and convincing evidence:”

(1) The patent applicant or owner made an affirmative misrepresentation of material fact, failed to disclose material information, or submitted false material information to the PTO. In the past, the Court has found errors or omissions ‘material’ that had nothing to do with patentability. In the most recent decisions, the Federal Circuit has erected a much higher barrier; namely, materiality turns on whether the PTO would have refused to issue the patent had it known of omitted prior art. This new test for materiality is known as the 'but for' test.

(2) The patent applicant or owner intended to deceive the PTO. The intent of the patent applicant or owner can be inferred from the circumstances. In the past, the Federal Circuit considered that the more material the misrepresentation, the lower the level of intent required to find inequitable conduct. The Federal Circuit recently overruled this position and held that bad intent must be demonstrated independently from materiality, which limits the scope of the 'inequitable conduct' defense.

If the trial court concludes that conduct of a patent applicant or owner amounts to "inequitable conduct," then the only remedy available to the court is to hold the entire patent and, on occasion, all related patents unenforceable.

D. Survey of Recent Cases

1. , 863 F.2d 867, 876 (Fed.

Cir. 1988) (en banc)

Kingsdown owned patents for an ostomy device. Kingsdown sued Hollister for infringement. Hollister defended based on inequitable conduct by Kingsdown during prosecution.

The prosecution had been complex, with multiple rejections, amendments, renumbering of 118 claims and an appeal. The examiner allowed claims after a final indefiniteness rejection, which was overcome by an amendment. Kingsdown then appealed other rejected claims. While the appeal was pending, Kingsdown’s attorney saw Hollister's ostomy device. Kingsdown withdrew its appeal and filed a continuation application using new counsel. The continuation application included the original language of the claim that was earlier rejected on indefiniteness grounds. In the continuation application, Kingsdown represented that the claim (and other claims) corresponded to a claim allowed in the earlier prosecution.

The trial court concluded that the error in the claim was ‘material’ because the language was required to be changed in the earlier prosecution and also because the earlier language would avoid a possible defense to literal infringement on the part of Hollister. The trial court concluded that Kingsdown’s attorney was grossly negligent and inferred intent to deceive based on that gross negligence and based on the advantage to Kingsdown in the infringement litigation from the claim erroneously allowed.

There was no real issue that an error was made. The question before the Federal Circuit was whether the element of ‘intent to deceive’ was present. The Circuit recited the facts and held that the circumstances demonstrated inattention to a ministerial matter, not intent to deceive. The circumstances recited (copying numerous claims into a continuation application) indicated that the error would be very easy to make.

The Federal Circuit also considered whether the breadth of the claim created an inference of intent. Here, other claims that were the subject of no error were broader than the claim in which the error appeared, removing any motive for deception on Kingsdown’s part.

The Court rejected precedent indicating that negligence alone could support a conclusion of intent to deceive. Said the Court:

…the involved conduct, viewed in light of all the evidence, including evidence indicative of good faith, must indicate sufficient culpability to require a finding of intent to deceive.

The Court concluded that the trial court finding of intent was clearly erroneous and reversed.

, 19

F.3d 1405 (Fed. Cir. 1994)

Samick filed a petition to ‘make special’ and thus obtain expedited examination of a design patent application for an electric grand piano. Samick alleged that its claim was being infringed. Such a petition required a declaration that the declarant had searched the prior art. The declaration was submitted and the petition granted. The patent subsequently was issued.

General Electro initiated a declaratory judgment action to challenge the design patent arguing ‘inequitable conduct.’ The defendants argued that Samick’s declarant had conducted no prior art search and lied about it under oath. The declarant did not hire a searcher and did not search PTO files. After a jury trial (which was not required due to the equitable nature of the relief sought), the jury found that the statements in the declaration were material and intentionally false. The use of the jury caused the Federal Circuit to give additional deference to the findings. The Court affirmed inequitable conduct.

225 F.3d 1318 (Fed. Cir. 2000)

Pharmacia supplied a material to PerSeptive. On evaluation of the materials, PerSeptive identified novel properties of the material. PerSeptive applied for a patent addressing the material and its novel characteristics. The attorney prosecuting the application identified the contribution of Pharmacia as a possible inventorship issue and disclosed the participation of Pharmacia in the specification, but stated that Pharmacia personnel were not inventors. The patent was issued to PerSeptive.

PerSeptive brought infringement action against Pharmacia and others. Pharmacia defended based on inequitable conduct, alleging that the inventorship for the patent was wrong.

The trial court concluded that inventorship was incorrect and should have included Pharmacia personnel. The law at the time allowed inventorship to be corrected if there was no deceptive intent on the part of the omitted inventors. The trial court found that the omitted inventors had no deceptive intent, but the included inventors did have deceptive intent based on a continuing pattern of misleading and incorrect statements to the PTO as to inventorship. The trial held that the patents were unenforceable due to inequitable conduct.

PerSeptive argued to the Federal Circuit that the claims were narrowed during prosecution, eliminating any issue of inventorship. The Federal Circuit majority (Judges Plager and Cleminger) brushed off the argument, saying that what was important was not inventorship for any patented claim, but false information about inventorship. Under this opinion, deceptive information, once supplied to the PTO, cannot be cured by narrowed claims and forever poisons any resulting patent.

The dissent (Judge Newman) takes the majority to task for misreporting the trial courts findings, for ignoring the effect of the amended claims on inventorship and for ignoring the facts of inventorship. (Judge Newman believes that inventorship was correctly investigated by the prosecuting attorney, was properly disclosed in the specification and stated in the declaration).

One rule here – too much information in the specification is not a good thing. The patents were lost because the majority found that statements in the specification relating to inventorship were false. If the statements had not been present in the specification, then there would have been nothing for the trial court or the majority to seize upon and the patent holder probably would have been allowed to correct inventorship under PTO procedures.

, 504 F.3d 1223 (Fed. Cir. 2007)

The technology at issue related to compact fluorescent light bulbs and ballasts for those bulbs. The ballast raises the frequency of alternating current to illuminate the gas-filled bulbs. The inventor fired his patent attorneys and prosecuted his fifteen patent applications .

The inventor entered into an agreement with Phillips by which the parties agreed that Phillips would take a license in the future and that no royalties would be due until the inventor had licensed the patents to competitors controlling 10% of the U.S. market. The trial court concluded that this was an obligation to license all of the patents to Phillips, that Phillips had more than 500 employees and that the inventor’s claim of small entity status after the date of the agreements was false. The trial court held all fifteen patents unenforceable due to inequitable conduct.

The inventor licensed all patents to an offshore non-profit, which then sublicensed the patents. The inventor argued that he was not obligated to pay large entity fees since his licensee was a small entity (the non-profit).

The Federal Circuit held as follows:

a. The inventor engaged in inequitable conduct by not disclosing that a declarant to overcome a rejection was an interested party, even though the declaration said nothing to mislead the PTO about his interest.

b. Inequitable conduct relating to one patent in a patent family properly invalidated other patents in the family.

c. Misrepresenting small entity status for issue fees and maintenance fees properly was inequitable conduct invalidating the patents.

d. Improper claims of priority to preceding applications when not all of the elements for priority were present properly were inequitable conduct.

e. Failure to disclose pending litigation as required by the MPEP properly supported a finding of inequitable conduct.

The Federal Circuit noted that the inventor’s explanations, taken in isolation, were not unreasonable. Taken in totality, the inventor’s intent was not to play ‘fair and square with the patent system.’ Judge Lourie authored the opinion.

(E.D. Wisc. 2007)

Decided July 24, 2007

After a patent holder filed multiple patent infringement actions, a defendant initiated an inter partes reexamination. During the reexamination, the patent owner produced a new sketch that showed conception of the invention predating a prior art reference, avoiding the reference. In the infringement action, the defendants presented evidence that the document was a forgery and did not predate the prior art reference as a matter of fact.

There was no controversy that the document was material – it avoided a crucial prior art reference. The trial court found as a matter of fact that the document was a forgery based on forensic evidence, thus showing a clear intent to deceive. The trial court then held the patent unenforceable. This case presents an instance of actual fraud similar to that of the early Supreme Court cases.

512 F. 3d 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (decided January 14, 2008)

Innogenetics held a patent for a method of detecting hepatitis ‘C’ virus. On summary judgment, the trial court rejected Abbott Laboratories’ inequitable conduct defense and awarded attorneys fees to Innogenetics due to exceptionality.

The basis of the claim was misrepresentation of a prior art reference. The reference was raised in the EPO as the closest prior art under EPO procedure, but Innogenetics argued before the EPO that it was nonetheless not important. The EPO limited the claims based on the reference. The reference was disclosed to the PTO, but the prosecuting attorney stated in the submission that it and other references “do not relate to the invention.” This was boilerplate language and the attorney did not review the reference. The trial court concluded that this statement was mere attorney argument and not a misrepresentation.

The Federal Circuit found no reason to reverse this conclusion. The award of attorneys fees to Innogenetics was upheld.

The discovery practices of Abbott Laboratories’ counsel apparently offended both the trial and appellate courts. The reference in question was disclosed on the last day of discovery when all depositions were concluded. This was only one of several hardball tactics employed by Abbott.

, 525 F.3d 1334 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (May 14, 2008)

Patents for a pharmaceutical product were held unenforceable due to failure to submit important experimental information. J. Rader dissented, saying that he did not find ‘clear and convincing’ evidence of an intent to deceive.

In the original prosecution, the examiner rejected claims as obvious, stating that the prior art was nearly identical and stating that in this circumstance the applicant must demonstrate that the product has properties that are unexpected or unobvious. Aventis argued to the examiner that the plasma half-life of the product was greater than that of the cited prior art reference. Aventis also presented expert declarations to the same effect, with tables of results attached. The patents subsequently issued based on the declarations and argument.

The defendants submitted ANDA applications to market generic versions of the drug and Aventis filed suit for infringement. Defendants argued invalidity based on inequitable conduct. Defendants presented evidence that the results presented to the PTO were for different dosages for the prior art and the invention, and that at the same dosage no half-life difference was apparent.

The trial court concluded that the failure to disclose the dosage discrepancy was material and that Aventis intended to deceive the PTO. On the first appeal, the Federal Circuit agreed that the dosage information was material but concluded that finding of intent to deceive was not supported by clear and convincing evidence, based on Aventis argument of inadvertent mistake. The Federal Circuit remanded to allow Aventis to present its case on inadvertence to the trial court. On remand, the trial court was unimpressed and found intent to deceive based on all the facts and circumstances. On the second appeal to the Federal Circuit, the majority determined that the trial court had not committed clear error.

Judge Rader dissented, stating that inequitable conduct was an ‘atomic bomb’ remedy and should be reserved for the most egregious cases of fraud. Judge Rader notes that , , substantially limited inequitable conduct, but that later cases the concept of ‘materiality’ has merged with intent, so that any material misstatement becomes an intent to deceive. Judge Rader gives the example of , , where an incorrect claim to small entity status was 'inequitable conduct.'

No. 2007-1399 (Fed.

Cir. 2008) (decided June 19, 2008)

The question in was whether incorrect statements in a petition to make special due to actual infringement (by the defendant) were ‘inequitable conduct’ rendering all patents derived from the application unenforceable. The applicant obtained accelerated review of the patent application because of the petition.

The trial court found that a petition to make special created inequitable conduct because the affidavit of the plaintiff’s lawyer falsely suggested that he had actually seen the infringing product and falsely suggested that the defendant copied the plaintiff’s product after seeing it at a trade show.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit rejected the argument that the conduct did not bear on the specific question of whether the invention was or was not patentable. The Court concluded that a misrepresentation was ‘material’ as a matter of law if the PTO acted upon it to expedite a review even when it did not relate to patentability.

The Court then considered inferences relating to bad intent drawn by the trial court from the factual statements in the petition. The Federal Circuit found it not reasonable to infer from the petition that the lawyer was representing that he actually had seen the offending product, when his analysis was based on information from brochures. The Federal Circuit also found that the trial court committed clear error in concluding that the plaintiff falsely told the PTO that the defendant copied the product. The Court also reversed the trial court’s finding of an exceptional case warranting attorney’s fees and costs.

The inequitable conduct decision gave the patent owner scant comfort, since the Federal Circuit invalidated the claims in question as obvious under .

533 F.3d 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (decided July 21, 2008)

EISAI held a patent for a pharmaceutical product. The defendants filed ANDAs for generic approval and EISAI filed suit for patent infringement. The defendants argued inequitable conduct based on a failure to disclose a co-pending patent application and upon failure to disclose prior art. The trial court refused to find inequitable conduct.

In an opinion by Judge Rader, the Federal Circuit affirmed, taking a narrow approach consistent with Rader’s dissent in , . Judge Rader reviews each of the trial judge’s decisions based on the facts and defers to the trial court, reaffirming his belief that inequitable conduct should be rarely applied.

No. 2007-1448 (Fed. Cir.

2008) (decided August 25, 2008)

The Federal Circuit reversed a trial court determination of inequitable conduct due to a clearly erroneous factual determination of the trial court.

The patents in question derive from the effort to create ‘safe’ cigarettes. The inventor believed that the presence of certain carcinogens in cured tobacco but not green tobacco was caused by microbes responding to low oxygen in the air around the tobacco leaves during curing. The invention was to control the oxygen levels around the leaves.

A consultant noted in a memo that Chinese tobacco using a reduced-oxygen curing method contained very little of the target chemical. The patent application did not disclose the memo on Chinese tobacco, but did disclose that the reduced oxygen technique in the U.S. generated high concentrations of the chemical. The prosecution changed hands. The new prosecuting attorneys discussed the memo in a series of e-mails and decided that the memo on Chinese tobacco was not material and need not be disclosed in a descendent patent application.

The trial court accepted the defendant’s argument that the plaintiff changed counsel to hide the unfavorable reference on Chinese tobacco, thus inferring intent to deceive. The trial court found that failure to submit the memo was inequitable conduct and the patents were unenforceable.

The Federal Circuit reversed, holding that the finding of inequitable conduct was not supported by ‘clear and convincing evidence.’ The Federal Circuit effectively found that the defendant’s theory was not evidence and that it had failed to introduce evidence to support its theory.

Although not stated in the opinion, the decision appears to reflect the balancing of materiality and intent by the Federal Circuit. Here, the memo on Chinese tobacco appears only marginally relevant and the Court required a higher showing of intent to deceive than it would have required for a clearly material reference.

(Fed. Cir. 2008) (decided September 29, 2008)

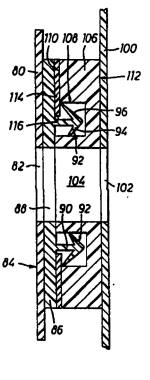

The technology at issue related to prevention of catastrophic release of toxic gases from storage bottles. The invention was a flow limiter comprising small, long orifices referred to as ‘multiple capillary passages.' The prior art included small orifices that were not long. Applicant did not disclose this prior art. Both the trial court and the Federal Circuit concluded that the prior art was highly material.

Synthesizing its own cases, the Federal Circuit noted that intent to deceive does not automatically flow from failure to disclose a material reference. There must be (a) a highly material information that is not provided to the PTO, (b) the applicant knew or should know about the information and about its materiality, and (c) the applicant provides no credible explanation for the failure to supply the information. The more material the withheld information, the less likely the applicant's explanation will be accepted as credible.

Two patent were at issue for inequitable conduct. In one patent prosecution, the applicant’s attorney made an affirmative representation during prosecution that the prior art did not disclose small orifices. Testimony revealed that the inventor and prosecuting attorney knew about the prior art reference during the prosecution of the application. The trial court found, and the Federal Circuit affirmed, that the affirmative statements indicated an ‘intent to deceive.’ The patent was held unenforceable by the trial court and the Federal Circuit.

For the second patent, a notice of allowability was issued prior to the time that the affirmative statement was made in the first patent application. The Federal Circuit found that the affirmative statements did not infect the second patent and did not support a finding of intent to deceive. The Federal Circuit did not apply the three-step test to determine whether omitting prior art amounts to 'inequitable conduct.'

(ND Ill. 2008), decided October 16, 2008

A patent owner initiated reexamination to bring prior art

to PTO as a result of litigation. In reexamination, the

owner submitted expert affidavits, including the owner’s own

affidavit. The owner’s affidavit stated that he had

previously had no contact with any of the other affiants.

The reexamination was because the application

pre-dated reexamination.

Judge Posner, sitting by designation, found that the

statements in the owner’s affidavit were deliberately false

and that he had solicited a proposal for engineering work

from one of the affiants a few months previously. The owner

paid for the proposal and apparently had several contacts

with the affiant.

Judge Posner considered whether the error was material and

whether a conclusion of ‘inequitable conduct’ was an

appropriate sanction. He concluded that the false statement

was central to the credibility of one of the four expert

reports and may have caused the examiner to reject the

report and perhaps the other reports as well.

The plaintiffs urged that as a sanction that the owner and the expert with the prior contact not be allowed to testify. Judge Posner noted that the appropriate sanction “normally” will be “cancellation” of the patents. Posner indicates that invalidation of only the claims at issue would be appropriate, but is not allowed by Federal Circuit precedent.

,

Fed. Cir.2008-1511, May 25, 2011

The Federal Circuit decision is a game changer in the area of inequitable conduct. The decision is , meaning that all of the court's judges participated in the decision and that the decision has greater precedential power than the usual decision by a three-judge panel of the Court.

The technology at issue related to test strips using electrochemical sensors to measure blood sugar in diabetics. During prosecution, Abbott, owner of the invention, argued to the PTO that the lack of a diffusion-limiting membrane distinguished the claimed invention from prior art and submitted affidavits to that effect. In a prior application before the European Patent Office, different Abbott attorneys had alleged that one of the items of prior art, also owned by Abbott, did not require a diffusion-limiting membrane. Abbott's earlier position before the European Patent Office contradicted its later affidavits and arguments to the PTO.

Becton Dickinson sued, arguing that Abbott engaged in 'inequitable conduct' by not disclosing the prior inconsistent position to the PTO. A panel of the Federal Circuit found the patent unenforceable due to inequitable conduct. The Federal Circuit reversed on the issue of inequitable conduct.

The Federal Circuit made clear that an action or failure to act of

the applicant must be both 'material' (that is, important) and also

demonstrate a 'specific intent to deceive' the PTO to amount to

inequitable conduct barring enforcement of a patent. The Federal

Circuit adopted a 'but for' test for materiality. If the patent

would not have been issued by the PTO 'but for' the act of the

applicant, then the act is 'material.' This is a high standard and

will avoid situations where a trivial, unimportant mistake by an

applicant renders the patent unenforceable.

The test does not address other false statements to the PTO,

such as whether the applicant is a large entity for purposes

of maintenance fees (see )

or whether the application is entitled to accelerated review

(see ).

The Federal Circuit also considered how much bad intent the patent

applicant must have to invalidate a patent. Where an applicant did not inform the PTO of a prior art

reference, which is the usual situation, there must be 'clear and

convincing' evidence of a 'specific intent to deceive.' The

'specific intent' can be inferred from all of the facts,

but is not affected by how material the misrepresentation

was. This intent

requirement presents a high burden to those

challenging a patent on inequitable conduct grounds.

The decision would appear to drive a stake through the heart of abuses of the inequitable conduct defense. However, the majority was razor-thin. The decision would have been very different if even one of the majority judges had decided the other way. We can expect this issue to be revisited after every change in Federal Circuit Court personnel.

14. Calcar v. Honda,

2009-1503 (Fed. Cir. June 27, 2011)

is the first application of the decision. Calcar sued Honda for infringement. Honda raised the inequitable conduct defense. The trial court found that three patents were unenforceable due to inequitable conduct, although an advisory jury found no inequitable conduct. The trial court inferred bad intent based on similarity of disclosure in the patent application to undisclosed prior-art manuals and based on contradictory testimony by an inventor.

The panel noted that although bad intent can be inferred, there are limits on that inference; namely, the bad intent "...must be the single most reasonable inference able to be drawn from the evidence...." The panel also noted that the intent and materiality requirements are independent and that a highly material omission does not lower the standard to demonstrate bad intent.

The Federal Circuit panel remanded the finding of inequitable conduct to the trial court for findings consistent with the 'but for' test for materiality of omitted disclosure and for findings of the specific intent of the inventors, all consistent with .

In the past, efforts by the Federal Circuit to restrict the 'inequitable conduct' defense have eroded quickly in subsequent decisions. The decision suggests that perhaps the reforms will stick this time. Of note, two of the judges on the three-judge panel dissented from the decision.

15.

Powell v Home

Depot U.S.A., Inc., 2010-1409 (Fed. Cir. November 14, 2011)

Powell developed a guard for the blade of circular saws used in Home Depot stores to cut lumber for customers. Powell installed a few prototypes in the stores for testing and applied for a patent. Powell petitioned for accelerated review based on his perceived obligation to manufacture and supply products covered by the patent to Home Depot. Powell's negotiations with Home Depot fell through and Home Depot copied the guards.

Although Powell's reason for expedited review was no longer correct, he did not notify the PTO. The PTO granted the petition for expedited review and issued the patent. Powell sued Home Depot for infringement. Home Depot defended based on inequitable conduct due to Powell's failure to notify the PTO that the reason for expedited review was not correct.

The Federal Circuit applied the 'but for' test for materiality from and concluded that Powell's error "obviously fails the but-for materiality standard" because it was not "affirmatively egregious misconduct."

E. Conclusions

1.. Before

The following were the conclusions of this memorandum before the Federal Circuit Court's decision, discussed above. These conclusions are now incorrect (see the following section), but illustrate the state of the law at the time that was decided:

a. The determination of whether particular conduct is ‘inequitable conduct’ rendering a patent unenforceable is highly fact-specific.

b. The finding of ‘inequitable conduct’ also is highly judge-specific, with different panels having very different views on whether conduct should invalidate a patent. Some commentators believe that the doctrine of inequitable conduct appears to be in retreat based on recent decisions, with the Federal Circuit more willing to find an error is not material or does not prove intent to deceive.1

c. Virtually ANY error or omission may trigger a finding of inequitable conduct. The more material the act, the more likely the court is to find that the act was intentional and that inequitable conduct exists. The list of acts that may render a patent unenforceable includes:

i. Wrongly claiming small entity status during prosecution or in payment of maintenance fees.

ii. Making an improper claim of priority.

iii. Making false statement in an affidavit about the interest of an affiant.

iv. Failing to affirmatively disclose that an affiant has an interest in the outcome.

v. Failure to disclose important parameters in testing of chemical or pharmaceutical inventions.

vi. Incorrect statements in a petition to make special.

vii. Failing to make a disclosure required by the MPEP, but apparently not by statute or regulation. This refers to the failure to disclose pending litigation.

viii. Making an incorrect claim of inventorship, even if the claim is later corrected or otherwise rendered moot due to amendments to the claims.

ix. Failing to disclose a prior art reference. The courts will look to the materiality of the reference, the knowledge of the applicant and any excuses for the failure. The more material the reference, the less likely that the court will accept the excuse.

x. Of course, providing fraudulent information to the PTO to overcome a reference or falsely denying that prior art exists.

d. Statements in an application that are not required may torpedo a patent, such as the gratuitous statements relating to inventorship in the specification.

2. After

After , the burdens on those attacking a patent based on failure to disclose an omitted prior art reference are much higher. The challenger must demonstrate both (1) that 'but for' the omitted prior art reference the PTO would have not issued the patent and (2) that the applicant knew of the prior art and specifically intended to deceive the PTO by withholding the reference. While deceptive intent can be inferred, deception must be the most reasonable explanation from all the other possible explanations for the applicant's actions.

We anticipate that the materiality and intent standards of Therasense will be applied to other incorrect actions of the applicant, such as incorrect statements of entity size for fee purposes and incorrect statements of priority.

Due to the narrow Therasense majority, we also anticipate that litigants will continue to raise 'inequitable conduct' as a defense and will hope that Court personnel changes or that the doctrine has eroded by the time that the case reaches the Federal Circuit.