Newsletter Issue 62 - April 2014

In this issue:

Artist's rights organizations

Trademark secrecy

Provisional patent applications

Ask Dr. Copyright ...

Dear Doc:

I write the songs that make the whole world sing. Unfortunately,

with all that songwriting, I really don't have the time to listen to

every radio station that plays my songs, every online store that

sells them, and every band, chorus, glee club, and lounge act that

covers them so that I can collect royalties. I have heard that there

are organizations that will do all of that for me, and even sue

people who don't pay up. What gives? I thought that "trolls" were

the bad guys, but this sounds like just what us musicians need in

order to make a living.

Barry M.

Dear BM:

The organizations you're referring to are called "Artists' Rights

Organizations" (AROs) and there are three big ones: Broadcast Music

Inc. (BMI), American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers

(ASCAP) and the Harry Fox Agency (HFA). Each one of these companies

is a nonprofit that licenses, collects, and distributes royalties on

behalf of musical copyright owners. BMI and ASCAP license public

performance rights to venues such as concert halls, bars,

restaurants, stores, etc.. HFA licenses "mechanical" rights, which

include the right to make CDs, records, tapes, and certain digital

products. In addition, there are more than 200 similar organizations

worldwide, and many have reciprocal agreements with one or more of

the US-based AROs. Not to confuse you more, but record labels also

license rights, and they have their own organization, the Recording

Industry Association of America (RIAA).

It's interesting to note that none of these companies writes any

music at all! Nor do they arrange it or perform it. They just

collect the royalties, and when someone refuses to pay up, they

bring law suits, relying on the Copyright Law (17 U.S.C. §101, et

seq.) which provides, among other things, that they can collect

attorneys' fees, and ask for statutory damages of up to $150,000 per

song played or copied. But, I hear you shout, "Last month, Doc, you

told us that this is pretty much exactly what companies that are

being called "patent trolls" do with patented inventions! They don't

invent widgets, and they don't make the widgets...they just offer to

license patent rights, and when someone refuses to pay the royalty,

they bring a law suit in which they demand a 'reasonable royalty'".

Yep...exactly! So there you have it. AROs are respected for the work

that they do to help musicians make a living by licensing rights,

collecting royalties, paying artists, and policing the use of the

rights by using the legal system. They are important because, to

quote the ASCAP website, "We know that there are many steps between

creation and compensation. A music creator is like a small business,

and we exist to ensure that ASCAP members are paid promptly and

fairly when their compositions are performed publicly." Now, to

quote one "patent troll" website, "Patent licensing can be an

effective and efficient way to maximize the profit potential of a

patent. A patent license agreement grants a third-party user of the

invention (an infringer) permission to practice the patented

invention in exchange for remuneration."

So there you have it. Patent trolls: BAD. Copyright trolls: GOOD.

Go figure!

If you have a question about how to license your intellectual

property, give one of the attorneys at LW&H a call. They're not

trolls, but they do understand how to help creative people protect

and profit from their creations, whether they are widgets, music, or

some other wonderful new thing that will be the next hit.

Keeping the Cat In the Bag When Filing a Trademark Application

One of the potential down sides of filing a trademark application

with the United States Patent and Trademark Office is that the

application, including the identity of the owner, is of public

record, accessible to anybody.

If secrecy is important to your company's marketing strategy then

filing a trademark application is not an act to be taken lightly.

So, if you are, say, Apple Computer, and you rely upon the

anticipation of the product announcement to build up market hype and

eventually sales, you will need to keep your trademark filings

secret until the product announcement. How do you do that without

spilling the beans?

The tried technique for maintaining secrecy is to create a dummy

corporation that no one will recognize for filing your trademark

applications. Once the need for secrecy evaporates, the dummy

corporation assigns the trademark to its true owner. Apple, in

fact, uses this technique.

AppleInsider recently reported that a

Delaware corporation called BrightFlash USA LLC recently filed a

host of trademark applications for the iWatch trademark. (Okay,

everybody knows or thinks they know that Apple will be releasing a

new product called the iWatch so what's the point of keeping it

secret? I guess it's because nobody knows for sure.)

It's not completely clear whether BrightFlash is actually an Apple

Computer surrogate, however, numerous trademark filings for iWatch

in the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union,

Australia, and Denmark, strongly suggest that Apple may be behind

the trademark applications. AppleInsider also reported that there

were numerous applications filed by BrightFlash for the iWatch

trademark in smaller countries. Just an interesting tidbit from

those who monitor trademark filings.

Provisional Patent Applications - File Early and Often

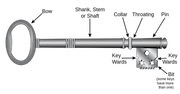

A provisional patent application is a temporary application that

provides patent-pending status for one year. The provisional

application can be a relatively low-cost way to preserve your patent

rights while you develop your invention. The protection offered by

a provisional patent application is only as good as the information

contained in the application and only addresses the invention as

disclosed in the application. The provisional application must

include enough information in the specification (the narrative part

of the application) and the drawings so that a person who is

knowledgeable in the technical field of the invention can make and

use the invention.

To have any continuing value, your provisional application must be

followed within one year by a full U.S. non-provisional (utility)

patent application. If the invention is one for which you will seek

international patent protection, your international patent

application(s) also must be filed within one year of the provisional

filing date.

If you develop improvements to your invention while your provisional

application is pending, the improvements are not protected. What

to do? File another provisional application addressed to the

improvements.