Newsletter Issue 36- February 2012

In this issue:

Putting books on the digital shelves

Patent justice is denied.

Facebook not so friendly.

Ipad trademark in dispute.

Ask Dr. Copyright

Ask Dr. Copyright

Dear Doc,

A few years ago, I remember reading that Google was digitizing every book in a bunch of libraries, and that soon, we would be able to search them all online. What's up with that?

Signed,

Still Waiting After All These Years

Dear SWAATY:

You're right - Google did start the Google Books Project in 2002,

and with the cooperation of several major libraries, including

Harvard, the University of Michigan, the New York Public Library,

Oxford and Stanford (collections estimated to contain 15 million

unique titles), they managed to scan a whole lot of books (more than

a million, and most long out of copyright.) Then the publishers got

wind of what they were doing, and before you could say Gutenberg,

the Author's Guild and McGraw-Hill sued Google for copyright

infringement. That was in 2005. In 2009, the parties reached a

settlement agreement which they submitted to the court. The

agreement provided rules under which publishers and authors could

"opt-out" of Google's project, and which distributed revenues from

advertising.

You see, a problem for everyone is that there are "orphan works"

which may or may not still be protected by copyright, but for which

no owner is known or even locatable. These books represent a small

fraction of the books in libraries, but like the proverbial few bad

apples, they spoil the whole batch. Google, for its part, agreed

that it would show only a catalog-card view of books that were still

protected by copyright, instead of allowing the entire book to be

read online or downloaded. All was well, until the judge rejected

the settlement, and there it sits. There are a lot of books at

Books.Google.com, but nobody seems to know what to do, and the

chances of getting the copyright laws changed to something a bit

more rational are, well, zero, given that movie studios, music

labels, and others seem to want to go back to that brief period

about 400 years ago when copyright lasted forever!

Along came the Internet Archive and the Long Now Foundation, and a

few other forward thinkers. How, they thought, could a digital

archive of every book in the world, be made to fit a copyright law

that is digitally ignorant? The result is OpenLibrary.org. The aim

is to have one web page for every book ever published, and to

operate just as a physical library does - lending each copy of the

book to one user at a time. Voila! Publishers have no legal basis to

complain (at least, not yet) and within just a few years, millions

of books have become available. In addition, using the copyright law

exception for the visually and perceptually impaired, just about

every book has been scanned and digitally recorded, so as works fall

into the public domain, they will be readily accessible. OpenLibrary

is not the best solution, but it's certainly a creative way to mesh

our 19th Century copyright laws with the technology of the 21st

Century. Check it out - there are lots of great books on the digital

shelves.

The "Doc"

'Justice Delayed is Justice Denied'*

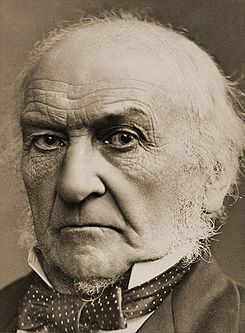

Unless the courts quickly resolve disputes, there is no justice. As former Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said:

"A sense of confidence in the courts is essential to maintain the fabric of ordered liberty for a free people and three things could destroy that confidence and do incalculable damage to society: that people come to believe that inefficiency and delay will drain even a just judgment of its value; that people who have long been exploited in the smaller transactions of daily life come to believe that courts cannot vindicate their legal rights from fraud and over-reaching; that people come to believe the law - in the larger sense - cannot fulfill its primary function to protect them and their families in their homes, at their work, and on the public streets."

The Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences ('BPAI') is denying

justice to patent applicants. The BPAI is charged with deciding

appeals by patent applicants from the rejection of patent claims by

the PTO. The BPAI backlog has gone from 1000 cases in 2006, to 4000

in 2008, to 18,000 in 2010. In early 2012 there are now 26,000

pending appeals of patent claim rejections. Appeals currently being

decided by the BPAI have been pending for about three years. The

BPAI gets further behind every day.

The effect of the increasing delay at the BPAI is to discourage

patent applicants from filing appeals and to shift power to patent

examiners. If an applicant cannot obtain speedy redress, then the

applicant will not appeal and patent examiners are free to make

arbitrary, wrong decisions. Of interest, when the BPAI rules, it

reverses the examiner in about one case in three.

Hopefully, help is in sight. The PTO is attempting to address the

BPAI backlog by doubling the number of patent judges at the BPAI.

The Department of Commerce is undertaking an audit of BPAI

operations to identify ways to speed appeals. Even with the efforts

of the PTO and Department of Commerce, we can expect the BPAI

backlog to linger for years.

Other changes at the BPAI include its disappearance, since it will

soon be replaced by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board under section

6 of the America Invents Act. The BPAI also has new procedural

rules.

*attributed to William E. Gladstone, 19th century British

politician, whose photo appears above.

Is Facebook Your Friend?

Do you have a Facebook Account? Do you realize that every time you

click the "Like" button for a product, service or website, Facebook

may distribute a paid advertisement ("a sponsored story") using your

name to all of your "Friends" suggesting that you are recommending

the product or service? While Facebook is described in the popular

media as a social networking site, it is, in reality, an advertising

business generating its revenue through the sale of advertising.

Zuckerberg (CEO of Facebook) has said: "...nothing influences people

more than a recommendation from a trusted friend. A trusted referral

influences people more than the best broadcaster message. A trusted

referral is the Holy Grail of advertising." Facebook's COO has said:

"...making your customers your marketers"..."is the illusive goal

we've been searching for." Consequently, Facebook is able to charge

a higher rate for the "sponsored stories."

Now Facebook has been sued in Federal Court in California over its

"sponsored story" advertising practice under statutory provisions

governing the right of publicity, unfair competition and fraudulent

and deceptive practices. California has a law on the books that says

everyone has the right to control how their name, photo, likeness,

and identity is used for commercial purposes, and such use may not

be done without their consent and a minimum ($750) payment. The

complaint makes several interesting points, not the least of which

is that Facebook employs a unique lexicon of doublespeak by

intentionally distorting the everyday meaning of words and

misleading members. Terms such as "friends," "like," "stories," and

"sponsor" may not mean the same to us as they do to Facebook. On

Facebook, "friends" are not really limited to close or intimate

associates; "like" does not necessarily imply an affinity for the

site/item; "sponsors" are really advertisers paying for the ads; and

"stories" are not written tales but are either items of friends

doings, or in the case of "sponsored stories" the advertisements

generated from members clicking the "Like" button. In addition,

plaintiffs allege that Facebook provides no avenue for opting out of

the sponsored stories.

An interesting side light to the case is that minors are allowed to

become members and have their names and images used in the

advertisements without requiring the consent of their parents or

guardians. Needless to say, Facebook has mounted a vigorous legal

challenge on both procedural and legal grounds to the accusations,

asserting a laundry list of defenses including: consent upon

registering under Facebook's terms; protection under the Federal

Communications Decency Act; First Amendment legitimate interest

protection under the Constitution; and protection under the

"newsworthy exception" for reporting on the activities of famous

people. (Would you believe that Facebook asserts that that members

are famous to their friends?)

On December 16, 2011, ruling on Facebook's motion to dismiss the

lawsuit, the Court refused to accept most of Facebook's arguments,

finding that plaintiffs had asserted valid causes of action under

the law. The Court reserved the question of whether members

consented to Facebook's practices The case is now in its discovery

phase.

In an interesting twist, just last week, two of the plaintiffs asked

to drop out of the case after Facebook's lawyers demanded discovery

depositions that threatened the plaintiffs with even more loss of

privacy. As of this writing, the Court has not ruled on their

request.

IPad Trademark Disputes Continue to Haunt Apple

Trademark lawyers often enjoy following trademark disputes involving

famous trademarks. If you haven't heard about Apple Computer's court

battle over ownership rights for the "iPad" trademark in China, read

on.

The Chinese owner of the "iPad" trademark is not Apple but a

beleaguered video display manufacturer known as Proview. In 2001,

Proview obtained rights to the "iPad" trademark in China around the

time it was developing a so-called Internet Personal Access Device

("IPAD acronym"), which only saw the brief light of day when it

proved to be a market failure. Later, in 2008, Proview fell into

rough financial times when the economy went south along with two of

its major customers, Polaroid and Circuit City, who filed for

bankruptcy.

In 2009 Apple was developing its own iPad device so it created a

company in the United Kingdom called "IP Application Development

Ltd.," (yet another IPAD acronym) established for the singular

purpose of acquiring trademark rights to "iPad". According to the

Chinese Court, a Proview subsidiary in Taiwan sold the "iPad"

trademark to Apple's UK company for $55,000.

Apple then sued Proview in China for wrongfully using the "iPad"

trademark. Proview fought back and in late 2011, the court issued

its opinion, which rejected Apple's lawsuit concluding that although

Apple purchased rights to "iPad" there was no formal transfer of

trademark rights. Apple, according to the court, purchased the

trademark from Proview's subsidiary, not from Proview itself, which

was unrepresented during the negotiations between Apple and the

Taiwanese company. Apple is appealing the decision.

It was widely reported that Proview would take its dispute to the

United States and on February 24th, the Wall Street Journal reported

that it had filed a lawsuit on February 17th in the Superior Court

of the State of California in Santa Clara County claiming that Apple

had committed fraud when it used Application Development Ltd., to

purchase the iPad trademark from Proview. What Proview hopes to gain

by suing Apple on its home turf is unclear but Apple may be eager to

settle to avoid disruption of its Chinese supply chains or sales to

Chinese consumers. It appears that Proview's comeback strategy is

built upon leveraging a lawsuit against the most famous technology

company in the world. Reuters news service reports that "[a]

Shanghai court this week threw out Proview's request to halt iPad

sales in the city. But the outcome of the broader dispute hinges on

a higher court in Guangdong, which earlier ruled in Proview's favour."

Apple, of course, maintains Proview refuses to honor its agreement.

Undoubtedly, Apple has enough cash to make this story go away and we

suspect that's just what will happen. The story also reinforces the

well established opinion that enforcing intellectual property

ownership rights in China may be problematical.