Newsletter Issue 33 - November 2011

In this issue:

Ask Dr. Copyright - Peer-to

Peer file sharing may be hazardous to your health.

'Best Mode' under the America Invents Act

The 'First Sale' doctrine and why you should not

rely on Google as your lawyer

Trademark infringement cases on the rise

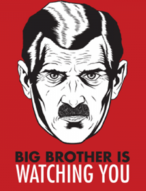

The privacy we give up for cell phone convenience.

Ask Dr. Copyright . . . Peer-to-Peer File Sharing

May Be Hazardous to Your Health

Ask Dr. Copyright . . . Peer-to-Peer File Sharing

May Be Hazardous to Your Health

Dear Doc:A friend of mine (if ya know what I mean) uses peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing software. She downloads cool things from the Internet, but then sorta-kinda-almost instantly erases them from her computer. Is this okay?

Signed,

MovieFan

Dear Fan:

Ahem...If I were your friend, I would stop doing that stuff. NOW! You see, those "cool things" are mostly protected by Copyright. While there are some movies and music that are not protected because they were made early enough that the registration has expired (think 1920s silent films) or whose owners failed to renew the copyright registration many years ago, it is really difficult to know which "cool things" are now in the "public domain" and which are still under registration. Making a mistake about that kind of thing can ruin your day.

Copyright owners and rights organizations now use pretty sophisticated computer programs to sniff around for unauthorized copying on the Internet, and they can track down users of P2P software programs right to the actual computer running the software, the time, date and Internet address used. Also, internet service providers are cooperating with rights owners in sending legal notices to P2P users.

One thing that you may not know is that when you use P2P software, you are not only downloading a copy of the files you see, but also your computer is being used to store and upload lots of other files that you may not see or even know are there. There have been cases where P2P users have been accused of distribution of child pornography because certain files were flowing from the Internet to their P2P software, being stored on their hard drives, and then re-transmitted to other P2P users - all without the knowledge of the person who used the P2P software in the first place.

So...think very hard. iTunes? NetFlix? HuluPlus? Or...you could make the Doc's day by continuing your outlaw ways, and getting one of those letters. If you do, however, the attorneys at LW&H deal with this kind of thing. Give them a call.

Lawrence Husick

'Best Mode' Under the America Invents Act

'Best Mode' Under the America Invents Act

'Best mode' is the requirement that a patent applicant disclose the

best way that the applicant knows to practice an invention. The

purpose of the 'best mode' requirement is to fulfill the public

disclosure goals of the patent system by preventing a patent

applicant from obtaining a patent while at the same time keeping the

best parts of the invention secret.

The 'best mode' requirement is present both under the

America

Invents Act, signed into law on September 16, 2011, and under prior

law. Section 15 of the Act changed the law so that failure by the

patent applicant to disclose 'best mode' is no longer a reason to

declare a patent invalid or unenforceable. This provision is

effective immediately and removes 'best mode' as an issue in

infringement and invalidity litigation. The change will make

litigation a little shorter and a little less expensive.

Is the best mode requirement now completely toothless?

Not quite,

according to

someone who took part in the discussions at the time.

'Best mode' is still a requirement of Federal law and failure to

disclose best mode potentially subjects the applicant to criminal

penalties and patent attorneys to disbarment, just like it did

before the Act. Do we expect Federal prosecutors to drop their cases

against bank robbers, terrorists and counterfeiters to pursue

less-than-completely-forthcoming inventors? Not likely.

Why is this change important for patent applicants? The chances of

being called out on a 'best mode' question just went from pretty

good to very low. While we would never advise a client to provide

anything other than 'best mode' (it's a requirement of Federal law,

after all), the applicant may wish to be more aggressive in

determining what is or is not 'best mode' and hence must be

disclosed in a patent application.

Robert Yarbrough

The 'First Sale' Doctrine and Why You Shouldn't Rely on Google (or Your Friends) as Your Lawyer

The 'First Sale' Doctrine and Why You Shouldn't Rely on Google (or Your Friends) as Your Lawyer

One of the exclusive rights in copyright granted to the creator of a work is the right to distribute it. For instance, if you self-publish a book -- a popular activity these days -- you also have the exclusive right to make copies and distribute them to whomever you want. The distribution right, however, is not unlimited. If I were to purchase one of your self-published books, the law permits me to resell it to whomever I want without violating your exclusive right of distribution. This is known as the "First Sale" doctrine -- codified in Section 109 (a) of the Copyright Act. The First Sale doctrine is important because it legitimizes the sales activities of used book stores, art galleries, and other establishments, which resell copyrighted works. But what are the limits of the First Sale doctrine? That was the question raised by a recent case before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in John Wiley and Sons, Inc. v. Supap Kirtsaeng, No. 09-4896-cv (August 15, 2011, 2nd Cir). It may have far-reaching implications.

In 2009, Supap Kirtsaeng, a Thai national, opened a used textbook business to support his educational studies in the United States. The business model was simple. He enlisted his friends and family in Asia to buy textbooks and ship them to him in the United States for resale on e-Bay. To ensure that he was acting legally, Kirtsaeng asked the opinion of his friends in Thailand and consulted "Google Answers" (now defunct). Apparently, these sources gave him the green light because his textbook selling activities continued and prospered. Kirtsaeng was so successful that he caught the eye of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. ("Wiley") -- the copyright owner -- who sued him in federal court for copyright infringement. Wiley based its lawsuit on Section 609(a) of the Copyright Act, which prohibits the importation of copyrighted works manufactured outside of the United States without the authorization of the copyright holder. At trial, the federal district court prohibited Kirtsaeng from raising the first sale doctrine as a defense to copyright infringement and as a result, the jury found in favor of Wiley and awarded it damages for intentional copyright infringement.

On appeal, the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the decision of the lower court. The court of appeals acknowledged that there was a tension between the First Sale doctrine, which gives rights to owners of copyrighted works and Section 609(a) of the Act, which takes them away if the works were manufactured outside of the United States. Nevertheless, it was persuaded by a recent decision of the United States Supreme Court in Quality King Distributors, v. L'anza Research International, Inc., which suggested that Section 609(a) was meant to give control to copyright owners over imported goods, which, by definition, are not "lawfully made" under the U.S. Copyright Act. Under the First Sale doctrine, the law requires that the goods be "lawfully made" under the Act.

Although a decision by the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit is not the law of the land, only decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court wear that title, it could potentially persuade other courts to decide cases in the same direction. The end result may have important implications for used book sellers, art galleries, libraries and any other establishment that may resell copyrighted works manufactured abroad. Of course the Kirtsaeng case also suggests that you shouldn't make important business decisions based on advise from non-experts even if they bear the "Google" name.

Adam Garson

Trademark Infringement Cases on the Rise

Trademark Infringement Cases on the Rise

Trademark owners are now litigating more than ever to preserve their

brand names and logos. They are taking aggressive stands with much

success. Here are some recent examples.Courts are enforcing the law of trademark infringement and trademark dilution to prevent unfair competition, a commercial tort designed to promote fair and honest competition. To preclude an action for trademark infringement, the mark, logo or design must not be "confusingly similar" to an existing mark, logo or design. A trademark is "confusingly similar" if it is likely to cause confusion amongst consumers as to the source of the product or service.

For example, In May 2011, Apple brought an infringement and dilution action against defendant Fei Lik Lam, a/k/a Phillip Lam for using the name whiteiphone4now.com. Apple's complaint states "The Apple Logo and iPhone Trademark are distinctive, iconic and famous trademarks that are instantly recognized as indicating products and services created, designed, manufactured, produced and/or provided by Apple." The court eventually found Lam's domain name to be confusingly similar to Apple's iphone in the sense that consumers may be confused that whiteiphone4now.com is part of Apple's line of products.

In 2008, Adidas filed an infringement case against Payless Shoes Source; a subsidiary of Collective Brands Inc. The Federal Court found Payless' sneakers with 2 and four parallel stripes infringed Adidas' sneakers and assessed Payless damages of $304.6 million. The Payless victory empowered Adidas to sue any sneaker company that sells sneakers bearing two, three or four stripes. Indeed, federal court records show that Adidas has approximately 325 pending infringement cases in the United States and approximately 45 settlement agreements. Most recently, in March 2011, Adidas sued small footwear manufacturing company Radii in federal court in Oregon.

In another infringement case, Facebook Inc., sued Teachbook.com LLC for trademark infringement for its use of the "Teachbook" domain name. In its defense, Teachbook argued that the word "book" was generic and could not be claimed by Facebook as a trademark. The court was not persuaded and on Oct 26, 2011, it refused to dismiss Facebook's complaint.

Similarly, businesses that dilute a famous mark may also be prevented from using their trademark. Trademark dilution refers to the concept where a trademark that is confusingly similar to a famous mark may not be used in a way that will lessen the uniqueness of the famous mark even though it may brand an entirely different product. That was one of the causes of action asserted by Apple in its case against whiteiphone4now.com discussed above. Foreign trademark law of dilution is very similar to that of the United States. For example, in November 2011, Lodha Garments in India was using the trademark 'Cadbeery'. Cadbury UK Ltd. and the Indian subsidiary filed a suit in the Delhi High Court against Lodha Garments on the grounds of "adopting a deceptively identical name to promote its product." The Delhi High Court granted an injunction against Lodha Garments. Here, the garment factory in India was not producing chocolates so as to directly infringe Cadbury's mark. However, they were diluting the famous mark 'Cadbury', renowned chocolate manufacturers, by using a similar name for garments.

New and start up businesses need to be wary of their choice of trademarks. A state and federal clearance search of the proposed mark is essential and consultation with a trademark attorney should be a high priority given the current climate and increase in trademark litigation.

Ash Tankha

Privacy We Give Up for Cell Phone Convenience

Privacy We Give Up for Cell Phone Convenience

Most of us use our cell phones for business and personal use. For instance, in the car returning from a family Thanksgiving celebration, my wife read her business e-mail, checked the weather, referred to a map for our location, and browsed for Black Friday sales. We all assume such phone activities are relatively private, but are they?

Recently, the ACLU obtained from the Justice Department a document guide for law enforcement that describes how major cell phone companies handle data and location information for phones using their service. It turns out that most carriers store usage information, albeit the kinds of data and the length of time the data is stored differs among carriers.

While carriers don't record calls, they keep a record of calls made and received. Verizon also stores for a year the identity of cell tower connections a phone makes; ATT has accumulated the same data since 2008. These data may be used to accurately determine where a phone is physically located at any moment during the day or night.

Web browsing information is not maintained by T-Mobile, but Verizon stores some web site identity information for up to a year. Sprint Nextel stores text messages for three months while Verizon only for three to five days. Other carriers do not keep text content, but instead store records of who texted who for a year or more. ATT preserves such data for seven years.

The ACLU takes the position that we all have a right to know how long records are kept. Do you agree?

Larry Weinberger